This blog is a note of APUE.

File Descriptor

To the kernel, all open files are referred to by file descriptors. A file descriptor is a non-negative integer.

By convention, UNIX System shells associate file descriptor 0 with the standard input, file descriptor 1 with the standard output, and file descriptor 2 with the standard error. This convention is used by the shells and many applications; it is not a feature of the UNIX kernel. These magic numbers should be replaced with the symbolic constants STDIN_FILENO, STDOUT_FILENO, and STDERR_FILENO, which are defined in the <unistd.h> header.

I/O Functions

Details of each function can be obtained by man 2 func_name.

open and openat

#include <fcntl.h> int open(const char *path, int oflag, ... /* mode_t mode */); int openat(int fd, const char *path, int oflag, ... /* mode_t mode */);

Return file descriptor if OK, -1 on error.

creat

#include <fcntl.h> int creat(const char *path, mode_t mode);

Return file descriptor opened for write-only if OK, -1 on error.

It is equivalent to

open(path, O_WRONLY | O_CREAT | O_TRUNC, mode);

close

#include <unistd.h> int close(int fd);

Return 0 if OK, -1 on error.

Closing a file also releases any record locks that the process may have on the file. When a process terminates, all of its open files are cloded automatically by the kernel.

lseek

#include <unistd.h> off_t lseek(int fd, off_t offset, int whence);

Return new file offset if OK, -1 on error.

Because negative offsets are possible, we should be careful to compare the return value from lseek as being equal to or not equal to -1, rather than testing whether it is less than 0.

lseek only records the current file offset within the kernel - it does not cause any I/O to take place. This offset is then used by the next read or write operation.

read

#include <unistd.h> ssize_t read(int fd, void *buf, size_t nbyte);

Return number of bytes read, 0 if end of file, -1 on error.

write

#include <unistd.h> ssize_t write(int fd, const void *buf, size_t nbytes);

Return number of bytes written if OK, -1 on error.

dup and dup2

#include <unistd.h> int dup(int fd); int dup2(int fd, int fd2);

Both return new file descriptor if OK, -1 on error.

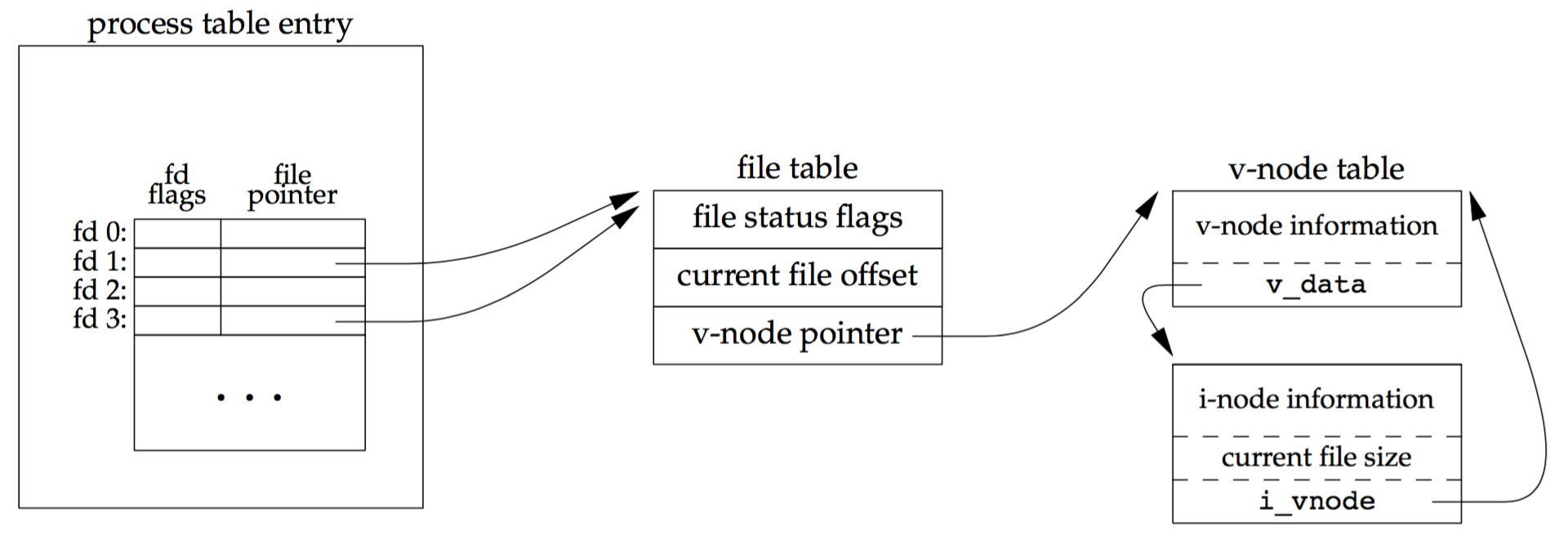

The new file descriptor returned by dup is guaranteed to be the lowest-numbered available file descriptor. With dup2, we specify the value of the new descriptor with the fd2 argument. If fd2 is already open, it is first closed. If fd equals fd2, then dup2 returns fd2 without closing it. Otherwise, the FD_CLOEXEC file descriptor flag is cleared for fd2, so that fd2 is left open if the process calls exec. Here gives a pictorial arrangement after calling dup.

Another way to duplicate a descriptor is with the fcntl function. Indeed,

dup(fd);

is equivalent to

fcntl(fd, F_FUPFD, 0);

, and

dup2(fd, fd2);

is equivalent to

close(fd2); fcntl(fd, F_DUPFP, fd2);

In the last case, the dup2 is not exactly the same as a close followed by an fcntl. The differences are:

dup2is an atomic operation.- There are some

errnodifferences betweendup2andfcntl.

fcntl

#include <unistd.h> int fcntl(int fd, int cmd, ... /* int arg */);

Return value depends on cmd if OK, -1 on error.

The fcntl function is used for five different purposes.

- Duplicate an existing descriptor ( cmd =

F_DUPFDorF_DUPFD_CLOEXEC) - Get/set file descriptor flags ( cmd =

F_GETFDorF_SETFD) - Get/set file status flags ( cmd =

F_GETFLorF_SETFL) - Get/set asynchronous I/O ownership ( cmd =

F_GETOWNorF_SETOWN) - Get/set record locks ( cmd =

F_GETLK,F_SETLK, orF_SETLKW)

File Sharing

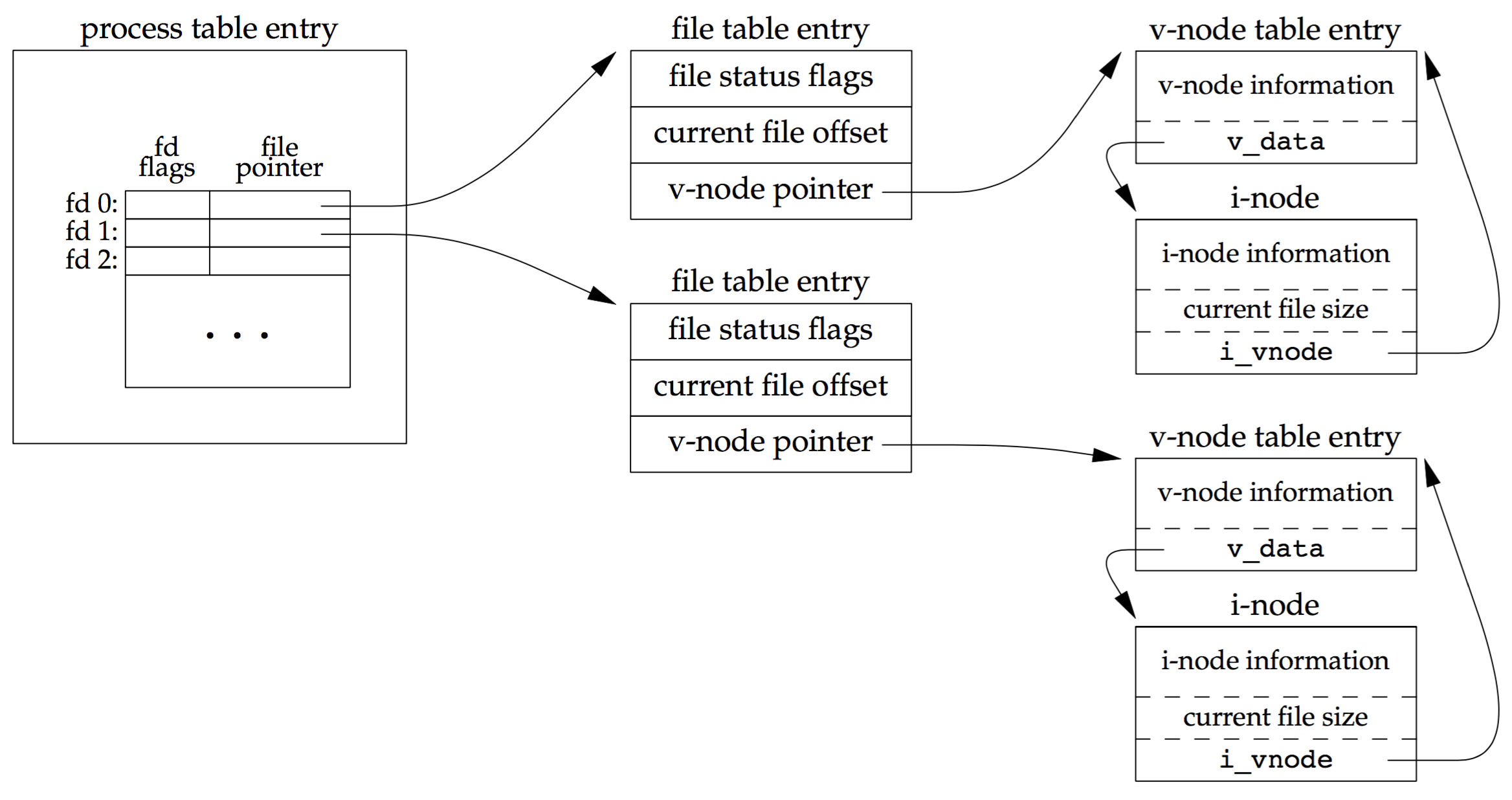

The kernel uses three data structures to represent an open file, and the relationships among them determine the effect one process has on another with regard to file sharing.

- Every process has an entry in the process table. Within each process table entry contains

- The file descriptor flags (currently there is only one fd flag: FD_CLOEXEC)

- A pointer to a file table entry

- The kernel maintains a file table for all open files. Each file table entry contains

- The file status flags for the file, such as read, write, append, sync, and nonblocking

- The current file offset

- A pointer to the v-node table entry for the file

- Each open file(or device) has a v-node structure that contains information about the type of file and pointers to functions that operate on the file. For most files, the v-node also contains the i-node for the file. This information is read from disk when the file is opened, so that all the pertinent information about the file is readily available.

The figure below shows a pictorial arrangement of these three tables for a single process that has two different file open.

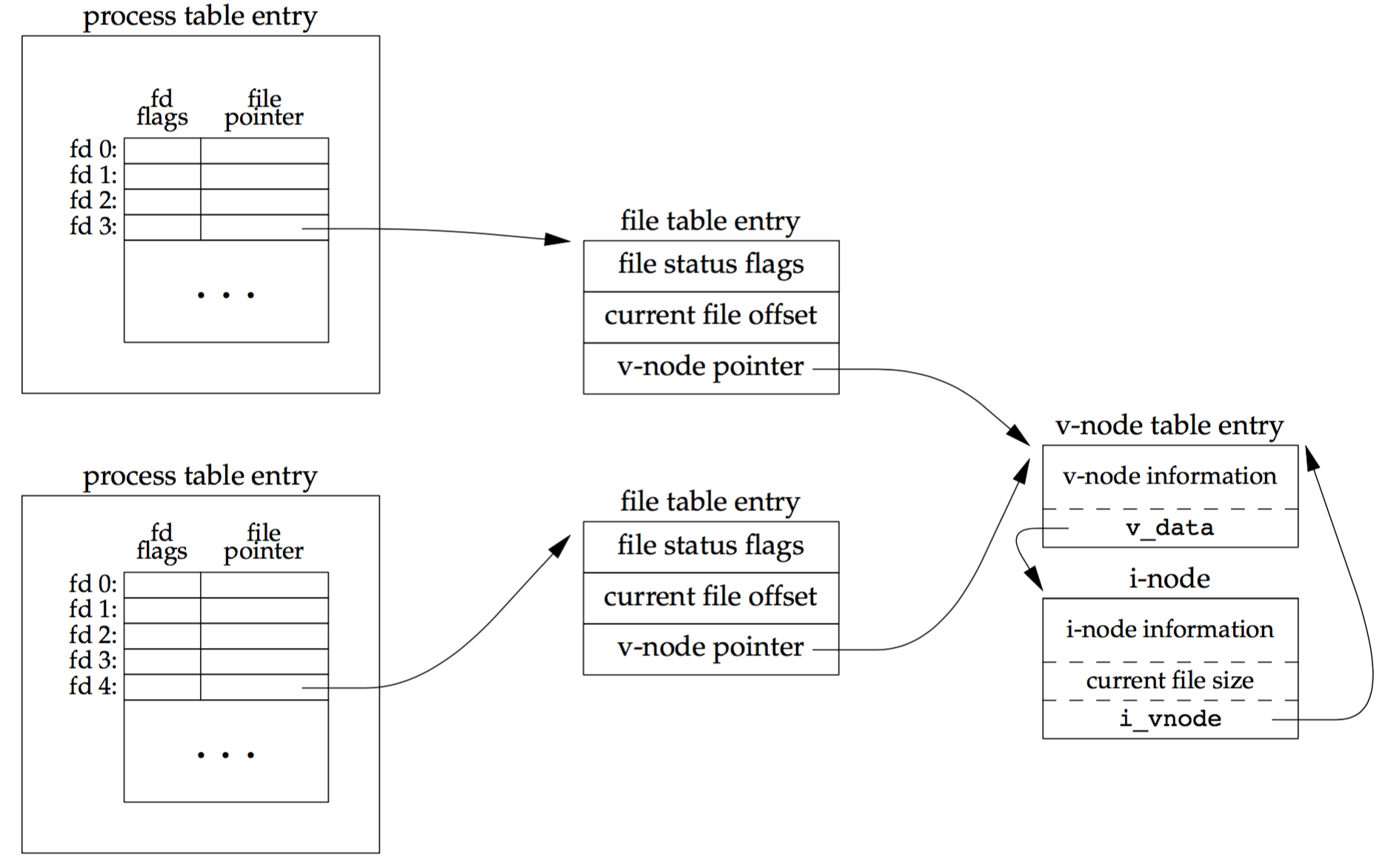

If two independent processes have the same file open, we could have the arrangement shown below.

The figure below shows a pictorial arrangement after calling newfd = dup(1), assuming that the next available descriptor is 3).

Given these data structures, we now explain what happens with certain operations.

- After each

writeis complete, the current file offset in the file table entry is incremented by the number of bytes written. If this causes the current file offset to exceed the current file size, the current file size in the i-node table entry is set to the current file offset(e.g., the file is extended). - If a file is opened with the O_APPEND flag, a corresponding flag is set in the file status flags of the file table entry. Each time a

writeis performed for a file with this append flag set, the current file offset in the file table entry is first set to the current file size from the i-node table entry. This forces everywriteto be appended to the current end of file. - If a file is positioned to its current end of file using

lseek, all that happens is the current file offset in the file table entry is set to the current file size from the i-node table entry. - The lseek function modifies only the current file offset in the file table entry. No I/O takes place.

/dev/fd

Newer systems provide a directory named /dev/fd whose entries are files named 0, 1, 2, and so on. Openning the file /dev/fd/n is equivalent to duplicating descriptor n, assuming that descriptor n is open.

The main use of the /dev/fd files is from the shell. It allows programs that use pathname arguments to handle standard input and standard output in the same manner as other pathnames.