- Streams and

FILEObjects - Standard Input, Standard Output, and Standard Error

- Buffering

- Opening a Stream

- Reading and Writing a Stream

- Line-at-a-Time I/O

- Binary I/O

- Positioning a Stream

- Formatted I/O

- FILE* to File Descriptor

- Temporary Files

- Memory Streams

- Alternative to Standard I/O

This blog is a note of APUE.

Streams and FILE Objects

Standard I/O file streams can be used with both single-byte and multibyte (“wide”) character sets. A stream’s orientation determines whether the characters that are read and written are single byte or multibyte. Initially, when a stream is created, it has no orientation.

#include <stdio.h> #include <wchar.h> int fwide(FILE *fp, int mode);

Return: positive if stream is wide oriented; negative if stream is byte oriented; 0 if stream has no orientation.

It performs different tasks, depending on the value of the mode argument.

- If the mode argument is negative,

fwidewill try to make the specified stream byte oriented. - If the mode argument is positive,

fwidewill try to make the specified stream wide oriented. - If the mode argument is zero,

fwidewill not try to set the orientation, but will still return a value identifying the stream’s orientation.

Note that fwide will not change the orientation of a stream that is already oriented.

When we open a stream, the standard I/O function fopen returns a pointer to a FILE object. This object is normally a structure that contains all the information required by the standard I/O library to manage the stream: the file descriptor used for actual I/O, a ponter to a buffer for the stream, the size of the buffer, a count of the number of characters currently in the buffer, an error flag, and the like. However, application software should never need to examine a FILE object. We just pass it as an argument to each standard I/O function.

Standard Input, Standard Output, and Standard Error

These streams are predefined and automatically available to a process, and they refer to the same files as the file descriptors STDIN_FILENO, STDOUT_FILENO, and STDERR_FILENO, respectively.

These three standard I/O streams are referenced through the predefined FILE * stdin, stdout, and stderr, which are defined in the stdio.h header.

Buffering

The goal of the buffering provided by the standard I/O library is to use the minimum number of read and write calls. Also, this library tries to do its buffering automatically for each I/O stream, obviating the need for the application to worry about it.

Three types of buffering are provided:

- Fully buffered. In this case, actual I/O takes place when the standard I/O buffer is filled.

- Line buffered. In this case, the standard I/O library performs I/O when a newline character is encountered on input or output.

- Unbuffered. The standard I/O library does not buffer the characters.

ISO C requires the following buffering characteristics:

- Standard input and standard output are fully buffered, if and only if they do not refer to an interactive device.

- Standard error is never fully buffered.

Most implementations default to the following types of buffering:

- Standard error is always unbuffered.

- All other streams are line buffered is they refer to a terminal device; otherwise, they are fully buffered.

We can change the buffering by calling either the setbuf or setvbuf function:

#include <stdio.h> void setbuf(FILE *restrict fp, char *restrict buf); int setvbuf(FILE *restrict fp, char *restrict buf, int mode, size_t size);

The latter returns 0 if OK, nonzero on error.

These functions must be called after the stream has been opened but before any other operation is performed on the stream.

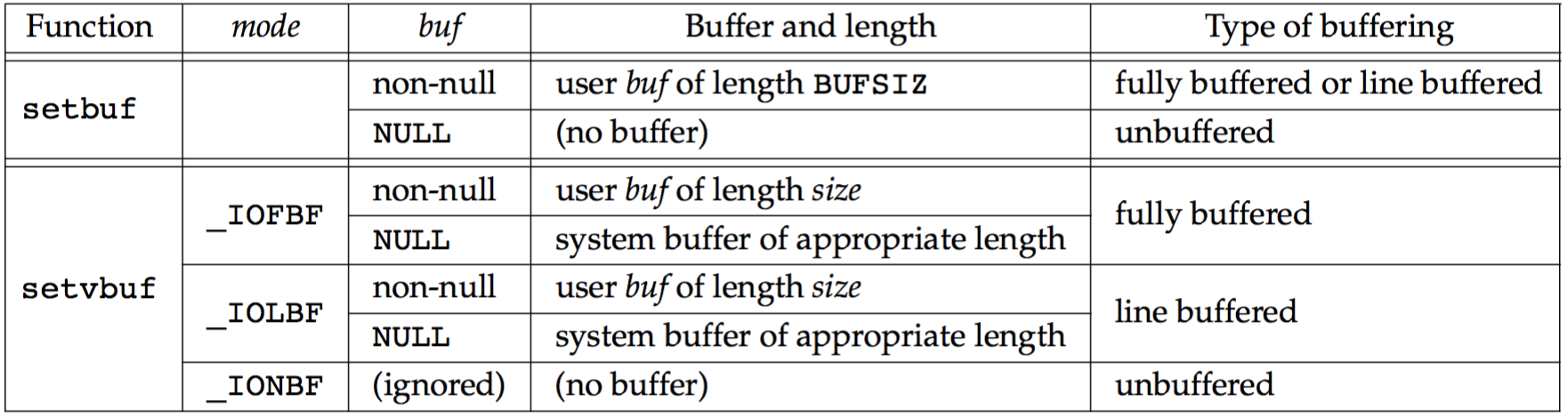

With setbuf, we can turn buffering on or off. To enable buffering, buf must point to a buffer of length BUFSIZ, a constant defined in stdio.h. To disable buffering, we set buf to NULL.

With setvbuf, we specify exactly which type of buffering we want. This is done with the mode argument:

_IOFBF |

fully buffered |

_IOLBF |

line buffered |

_IONBF |

unbuffered |

If we specify an unbuffered stream, the buf and size arguments are ignored. If we specify fully buffered or line buffered, buf and size can optionally specify a buffer and its size. If the stream is buffered and buf is NULL, the standard I/O library will automatically allocate its own buffer of the appropriate size for the stream. By appropriate size, we mean the value specified by the constant BUFSIZ.

Here is the summary of these two functions.

We should let the system choose the buffer size and automatically allocate the buffer. When we do this, the standard I/O library automatically releases the buffer when we close the stream.

At any time, we can force a stream to be flushed.

#include <stdio.h> int fflush(FILE *fp);

Return 0 if OK, EOF on error.

The fflush function causes any unwritten data for the stream to be passed to the kernel. As a special case, if fp is NULL, fflush causes all output streams to be flushed.

Opening a Stream

#include <stdio.h> FILE *fopen(const char *restrict pathname, const char *restrict type); FILE *freopen(const char *restrict pathname, const char *restrict type, FILE *restrict fp); FILE *fdopen(int fd, const char *type);

They all return FILE * if OK, NULL on error. For more information, you can man fopen.

The differences in these three functions are as follows:

- The

fopenfunction opens a specified file. - The

freopenfunction opens a specified file on a specified stream, closing the stream first if its is already open. If the stream previously has an orientation,freopenclears it. This function is typically used to open a specified file as one of the predefined streams: standard input, standard output, or standard error. - The

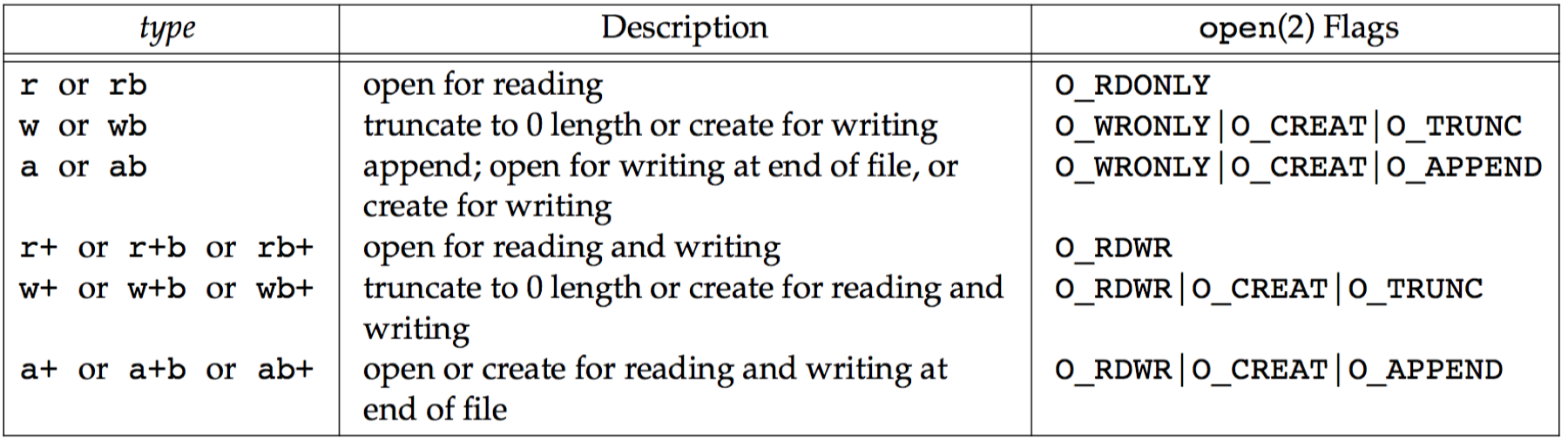

fdopenfunction takes a existing file descriptor, which we could obtain from theopen,dup,dup2,fcntl,pipe,socket,socketpair, oracceptfunctions, and associates a standard I/O stream with the descriptor. This function is often used with descriptors that are returned by the functions that create pipes and network communication channels. Because these special types of files cannot be opened with she standard I/Ofopenfunction, we have to call the device-specific function to obtain a file descriptor, and then associate this descriptor with a standard I/O stream usingfdopen. Here is the type argument for opening a standard I/O stream.

When a file is opened with a type of append, each write will take place at the then current end of file. If multiple processes open the same file with the standard I/O append mode, the data from each process will be correctly written to the file.

When a file is opened for reading and writing (the plus sign in the type), two restrictions apply:

- Output cannot be directly followed by input without an intervening

fflush,fseek,fsetpos, orrewind. - Input cannot be directly followed by output without an intervening

fseek,fsetpos, orrewind, or an input operation that encounters an end of file.

An open stream is closed by calling fclose.

#include <stdio.h> int fclose(FILE *fp);

Return 0 if OK, EOF on error.

Any buffered output data is flushed before the file is closed. Any input data that may be buffered is discarded. If the standard I/O library had automatically allocated a buffer for the stream, that buffer is released.

Reading and Writing a Stream

Once we open a stream, we can choose from among three types of unformatted I/O:

- Character-at-a-time I/O. We can read or write one character at a time, with the standard I/O functions handling all the buffering, if the stream is buffered.

- Line-at-a-time I/O. If we want to read or write a line at a time, we use

fgetsandfputs. Each line is terminated with a newline character, and we have to specify the maximum line length that we can handle when we callfgets. - Direct I/O. This type of I/O is supported by the

freadandfwritefunctions. For each I/O operation, we read or write some number of objects, where each object is of a specified size. These two functions are often used for binary files where we read or write a structure with each operation.

Input Functions

#include <stdio.h> int getc(FILE *fp); int fgetc(FILE *fp); int getchar(void);

They all return next character if OK, EOF on end of file or error.

The function getchar is defined to be equivalent to getc(stdin). The difference between getc and fgetc is that getc can be implemented as a macro (which is the case in OS X), whereas fgetc cannot be implemented as a macro. This means three things:

- The argument to

getchsould not be an expression with side effects, because it could be evaluated more than once. - Since

fgetcis guaranteed to be a function, we can take its address. This allows us to pass the address offgetcas an argument to another function. - Calls to

fgetcprobably take linger than calls togetc, as it usually takes more time to call a function.

These three functions return the next character as an unsigned char converted to an int. The constant EOF in

stdio.his required to be a negative value. Its value is often -1. This representation also means that we cannot store the return vaule from these three functions in a character variable and later compare this value with the constant EOF.

Note that these functions return the same value whether an error occurs or the end of file is reached. To distinguish between the two, we must call either ferror or feof:

#include <stdio.h> int ferror(FILE *fp); int feof(FILE *fp);Both return nonzero (true) if condition is true, 0 (false) otherwisevoid clearerr(FILE *fp);

In most implementations, two flags are maintained for each stream is the FILE object:

- An error flag

- An end-of-file flag

Both flags are cleared by calling clearerr.

After reading from a stream, we can push back characters by calling ungetc.

#include <stdio.h> int ungetc(int c, FILE *fp);

Return c if OK, EOF on error.

Pushback is often used when we’re reading an input stream and breaking the input into words or tokens of some form. Sometimes we need to peek at the next character to determine how to handle the current character. It’s then easy to push back the character that we peeked at, for the next call to getc to return.

Output Functions

#include <stdio.h> int putc(int c, FILE *fp); int fputc(int c, FILE *fp); int putchar(int c);

They all return c if OK, EOF on error.

Line-at-a-Time I/O

#include <stdio.h> char *fgets(char *restrict buf, int n, FILE *restrict fp); char *gets(char *buf);

Both return buf if OK, NULL on end of file or error.

The gets function reads from standard input, whereas fgets reads from the specified stream. With fgets, we have to specify the size of the buffer, n. This function reads up through and including the next newline, but no more than n - 1 characters, into the buffer. The buffer is terminated with a null byte. If the line, including the terminating newline, is longer than n - 1, only a partial line is returned, but the buffer is always null terminated. Another call to fgets will read what follows on the line.

The gets function should never be used. The problem is that it doesn’t allow the caller to specify the buffer size. This allows the buffer to overflow if the line is longer than the buffer, writing over whatever happens to follow the buffer in memory. An additional difference with gets is that it doesn’t store the newline in the buffer, as fgets does.

#include <stdio.h> int fputs(const char *restrict str, FILE *restrict fp); int puts(const char *str);

Both return non-negative value if OK, EOF on error.

The function fputs writes the null-terminated string to the specified stream. The null byte at the end is not written. Not that this need not be line-at-a-time output. The putsfunction writes the null-terminated string to the standard output, without writing the null byte. But puts then writes a newline character to the standard output.

Always use

fputsandfgets.

Binary I/O

#include <stdio.h> size_t fread(void *restrict ptr, size_t size, size_t nobj, FILE *restrict fp); size_t fwrite(const void *restrict ptr, size_t size, size_t nobj, FILE *restrict fp);

Both return the number of objects read or written.

If we;re doing binary I/O, we often would like to read or write an entire structure at a time. To do this using getc or putc, we have to loop through the entire structure, one byte at a time, reading or writing each byte. We can’t use the line-at-a-time functions, since fputs stops writing when it hits a null byte, and there might be null bytes within the structure, Similarly, fgets won’t work correctly on input if any of the data bytes are null or newlines. These functions have two common uses:

- Read or write a binary array. For example, to write elements 2 through 5 of a floating-point array, we could write

1

2

3

4

5

float data[10];

if(fwrite(&data[2], sizeof(float), 4, fp) != 4){

printf("fwrite error");

}

- Read or write a structure. For example, we could write

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

struct {

short count;

long total;

char name[NAMESIZE];

} item;

if(fwrite(&item, sizeof(item), 1, fp) != 1){

printf("fwrite error");

}

To make the code above work, you need to use

-O0option to disable any optimization.

There are two problems using these two functions:

- The offset of a member within a structure can differ between compilers and systems because of different alignment requirements. Indeed, some compilers have an option allowing structures to be packed tightly, to save space with a possible runtime performance penalty, or aligned accurately, to optimize runtime access of each member, This means that even on a single system, the binary layout of a structure can differ, depending on compiler options.

- The binary formats used to store multibyte integers and floating-point values differ among machine architectures.

Positioning a Stream

#include <stdio.h> long ftell(FILE *fp);Return current file position indicator if OK, -1L on errorint fseek(FILE *fp, long offset, int whence);Return 0 if OK, -1 on errorvoid rewind(FILE *fp); off_t ftello(FILE *fp);Return current file position indicator if OK, (off_t)-1 on errorint fseeko(FILE *fp, off_t offset, int whence);Return 0 if OK, -1 on errorint fgetpos(FILE *restrict fp, fpos_t *restrict pos); int fsetpos(FILE *fp, const fpos_t *pos);Both return 0 if OK, nonzero on error

There are three ways to position a standard I/O stream:

- The two functions

ftellandfseek. They assume that a file’s position can be stored in a long integer. - The two functions

ftelloandfseeko. They were introduced in the Single UNIX Specification to allow for file offsets that might not fit in a long integer. - The two functions

fgetposandgsetpos. They were introduced by ISO C. They use an abstract data type,fpos_t, that records a file’s position. This data type can be made as big as necessary to record a file’s position.

When porting applications to non-UNIX systems, use fgetpos and fsetpos.

Formatted I/O

### Formatted Output

#include <stdio.h> int printf(const char *restrict format, ...); int fprintf(FILE *restrict fp, const char *restrict format, ...); int dprintf(int fd, const char *restrict format, ...);All three return the number of characters output if OK,int sprintf(char *restrict buf, const char *restrict format, ...);

negative value if output errorReturn the number of characters stored in array if OK,int snprintf(char *restrict buf, size_t n, const char *restrict format, ...);

negative value if encoding errorReturn the number of characters that would have been stored in array

if buffer was large enough, negative value if encoding error

The printf function writes to the standard output, fprintfwrites to the specified stream, dprintf writes to the specified file descriptor, and sprintf places the formatted characters in the array buf. The sprintf function automatically appends a null byte at the end of the array, but this null byte is not included in the return value.

Note that it’s possible for sprintf to over flow the buffer pointed to by buf. The caller is responsible for ensuring that the buffer is large enough. Because buffer overflows can lead to program instability and even security violations, snprintf was introduced. With it, the size of the buffer is an explicit parameter; any characters that would have been written past the end of the buffer are discarded instead. As with sprintf, the return value doesn’t include the terminating null byte.

The format specification conforms to a conversion specification:

%[flags][fldwidth][precision][lenmodifier]contype

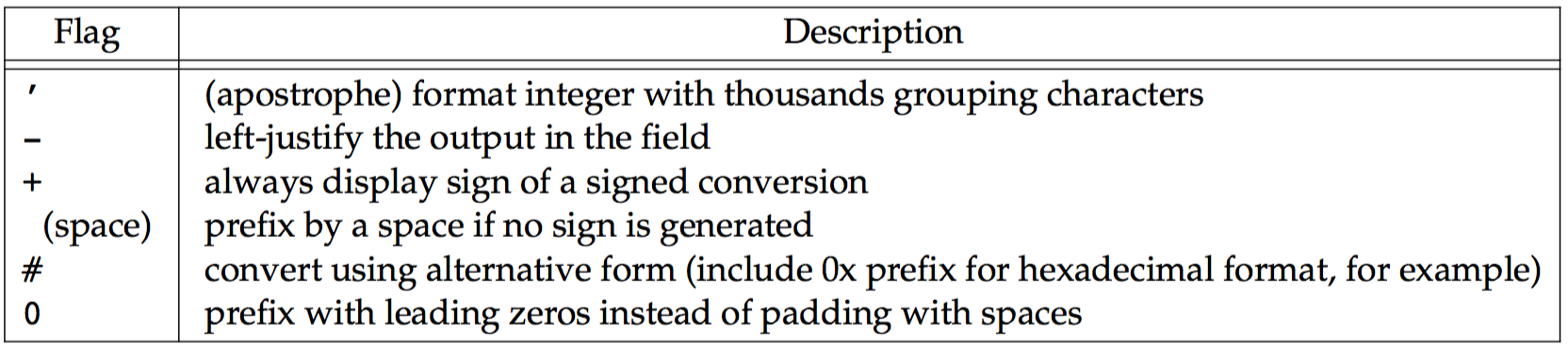

The flags are summarized below:

The fldwidth component specifies a minimum field with for the conversion. If the conversion results in fewer characters, it is padded with spaces. The field width is a non-negative decimal integer or an asterisk.

The precision component specifies the minimum number of digits to appear for integer conversions, the minimum number of digits to appear to the right of the decimal point for floating-point conversions, or the maximum number of bytes for string conversion. The precision is a period (.) followed by an optional non-negative decimal integer or an asterisk.

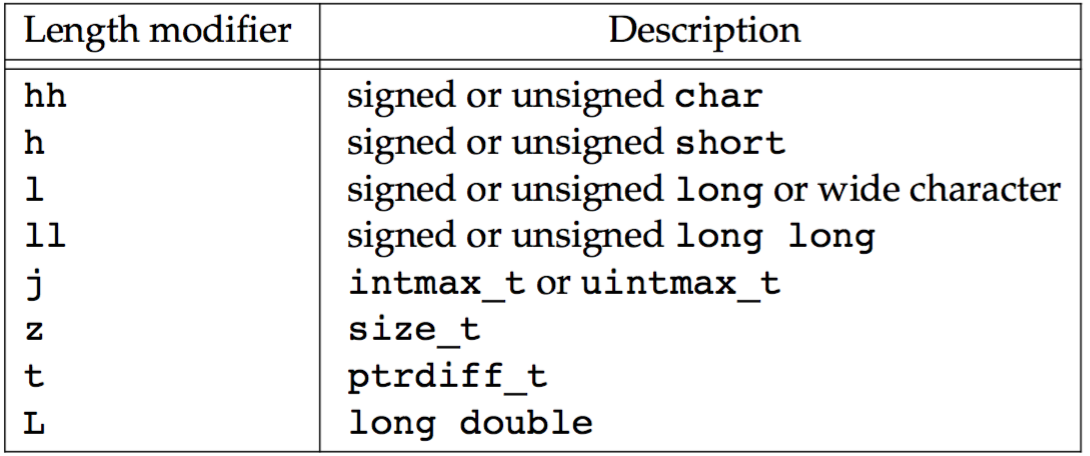

The lenmodifier component specifies the size of the argument. Possible values are summarized below:

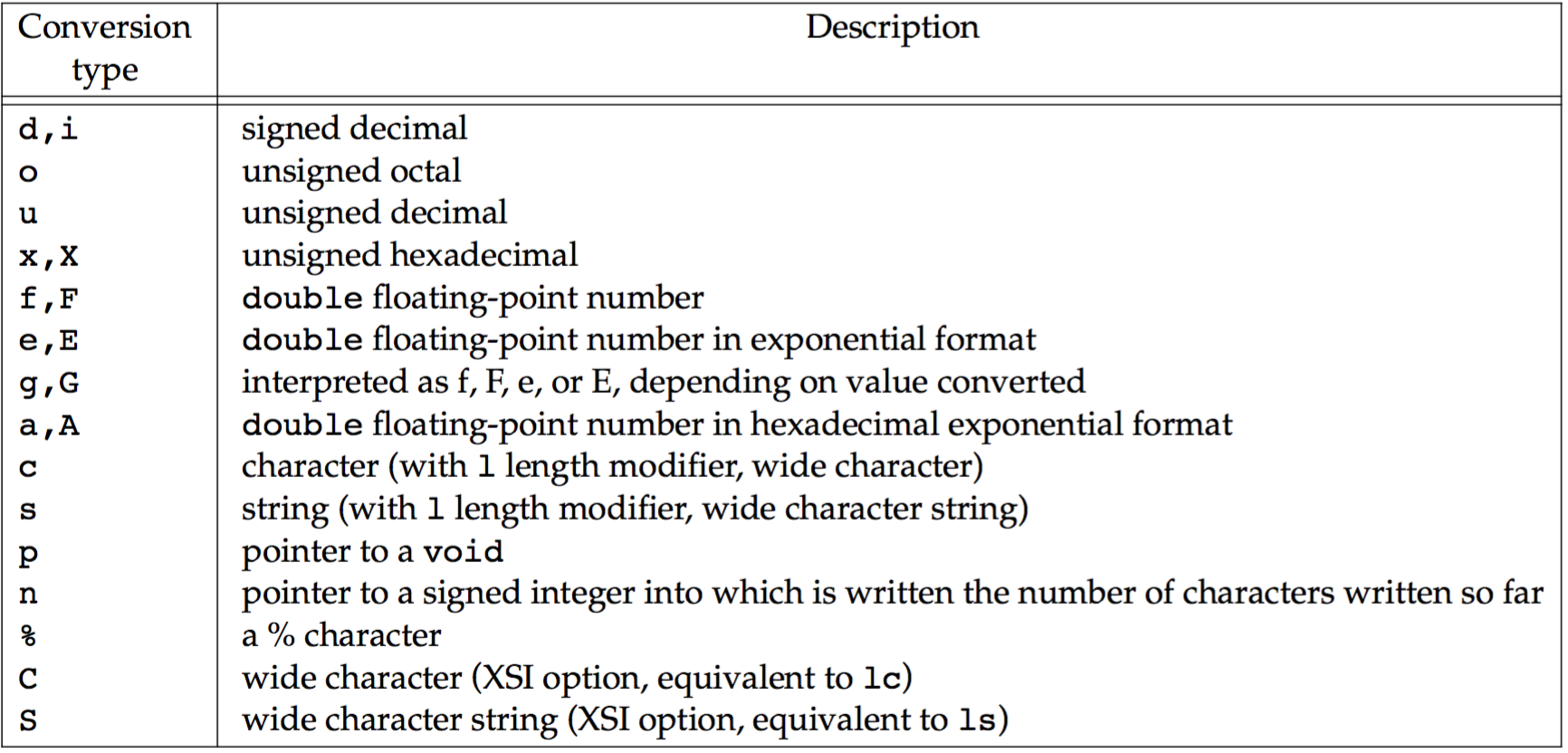

The convtype component is not optional. It is summarized below:

The following five variants of the printf family are similar to the previous five, but the variable argument list (…) is replaced with arg.

#include <stdarg.h> #include <stdio.h> int vprintf(const char *restrict format, va_list arg); int vfprintf(FILE *restrict fp, const char *restrict format, va_list arg); int vdpritnf(int fd, const char *restrict format, va_list arg); int vsprintf(char *restrict buf, const char *restrict format, va_list arg); int vsnprintf(char *restrict buf, size_t n, const char *restrict format, va_list arg);

Formatted Input

#include <stdio.h> int scanf(const char *restrict format); int fscanf(FILE (restrict fp, const char *restrict format, ...); int sscanf(const char *restrict buf, const char *restrict format, ...);All three return the number of input items assigned,

EOF if input error or end of file before any conversion

There are three optional components to a conversion specification:

%[*][fldwidth][m][lenmodifier]convtype

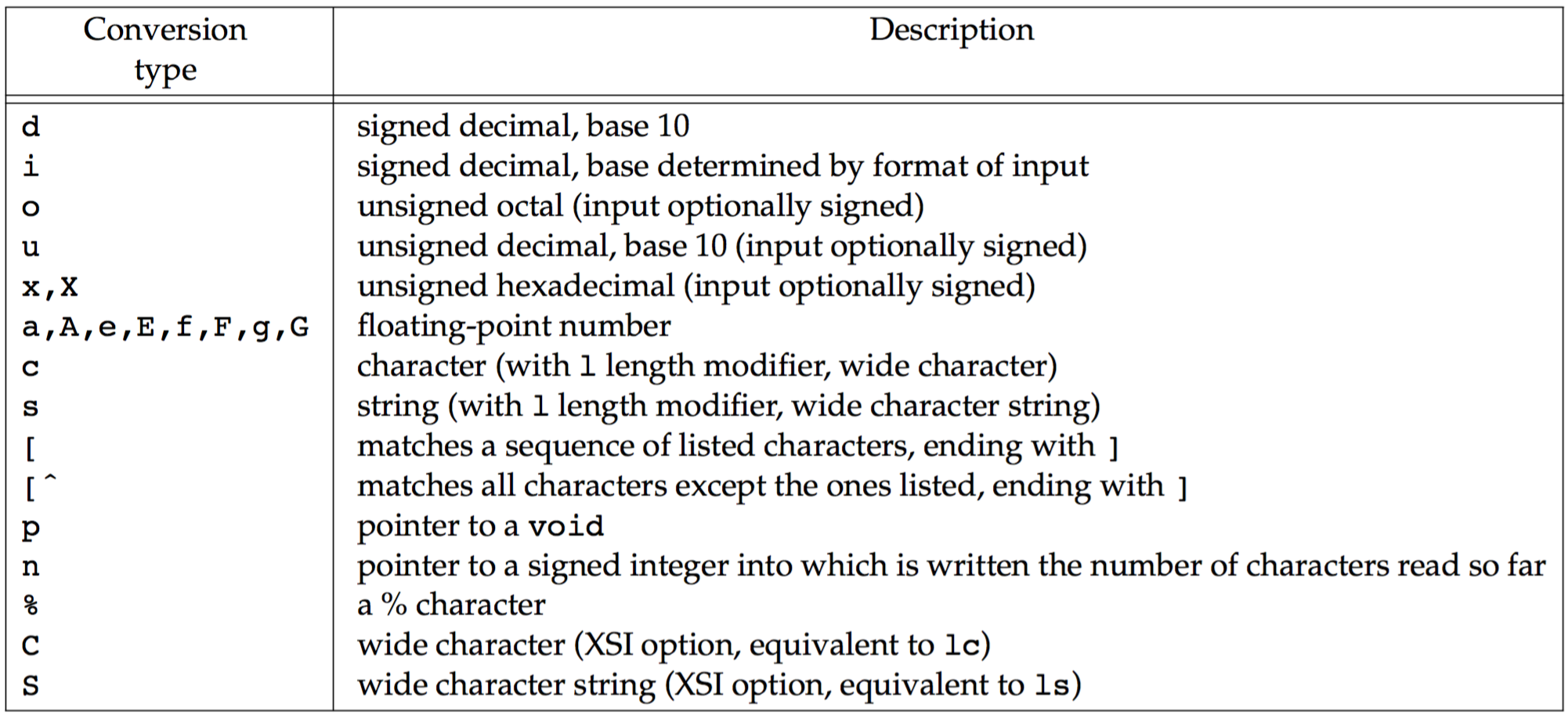

The optional leading asterisk is used to suppress conversion. Input is converted as specified by the rest of the conversion specification. The fldwidth and lenmodifier components are the same as the printf family. The convtype field is similar to the conversion type field used by the printf family, but there are some differences. One difference is that results that are stored in unsigned types can optionally be signed on input. For example, -1 will scan as 4294967295 into an unsigned integer. The figure below summarizes the conversion types supported by the scanf family:

The optional m character between the field width and the length modifier is called the assignment-allocation character. It can be used with the %c, %s, and %[ conversion specifiers to force a memory buffer to be allocated to hold the converted string. In this case, the corresponding argument should be the address of a pointer to which the address of the allocated buffer will be copied. If the call succeeds, the caller is responsible for freeing the buffer by calling the free function when the buffer is no longer needed.

The scanf family also supports functions that use variable argument lists:

#include <stdarg.h> #include <stdio.h> int vscanf(const char *restrict format, va_list arg); int vfscanf(FILE *restrict fp, const char *restrict format, va_list arg); int vsscanf(const char *restrict buf, const char *restrict format, va_list arg);

FILE* to File Descriptor

#include <stdio.h> int fileno(FILE *fp);

Temporary Files

#include <stdio.h> char *tmpnam(char *ptr);Returns pointer to unique path nameFILE *tmpfile(void);Returns file pointer if OK, NULL on error

#include <stdlib.h> char *mkdtemp(char *template);Returns the pointer to directory name if OK, NULL on errorint mkstemp(char *template);Returns file descriptor if OK, -1 on error

Unlike tmpfile, the temporary file created by mkstemp is not removed automatically for us. If we want to remove it from the file system namespace, we need to unlink it ourselves.

Use of tmpnam and tempnam does have at least one drawback: a window exists between the time that the unique path name is returned and the time that an application creates a file with that name. During this timing window, anther process can create a file of the same name, The tmpfile amd mkstemp functions should be used instead, as they don’t suffer from this problem.

Memory Streams

The standard I/O library buffers data in memory, so operations such as character-at-a-time I/O and line-at-a-time I/O are more efficient (compared with what?). We can provide our own buffer for for the library to use by calling setbuf or setvbuf. In Version 4, the Single UNIX Specification added support for memory streams. There are standard I/O streams for which ther are no underlying files, although they are still accessed with FILE pointers. All I/O is done by transferring bytes to and from buffers in main memory.

#include <stdio.h> FILE *fmemopen(void *restrict buf, size_t size, const char *restrict type); FILE *open_memstream(char **bufp, size_t *sizep); #include <wchar.h> FILE *open_wmemstream(wchar_t **bufp, size_t *sizep);

All return a stream pointer if OK, NULL on error.

The open_memstream function creates a stream that is byte oriented, and the open_wmemstream function creates a stream that is wide oriented. These two functions differ from fmemopen in several ways:

- The stream created is only open for writing.

- We can’t specify our own buffer, but we can get access to the buffer’s address and size through the bufp and sizep arguments, respectively.

- We need to free the buffer ourselves after closing the stream.

- The buffer will grow as we add bytes to the stream.

We must follow some rules, however, regarding the use of the buffer address and it length:

- The buffer address and length are only valid after a call to

fcloseorfflush. - These values are only valid until the next write to the stream or a call to

fclose. Because the buffer can grow, it may need to be reallocated. If this happens, then we will find that the value of the buffer’s memory address will change the next time we callfcloseorfflush.

Memory streams are well suited for creating strings, because they prevent buffer overflow. They can also provide a performance boost for functions that take standard I/O stream arguments used for temporary files, because memory streams access only main memory instead of a file stored on disk.

Alternative to Standard I/O

The standard I/O library is not perfect. One inefficiency inherent in the standard I/O library is the amount of data copying that takes place. When we use the line-at-a-time functions, fgets and fputs, the data is usually copied twice: once between the kernel and the standard I/O buffer (when the corresponding read or write is issued) and again between the standard I/O buffer and our line buffer. The Fast I/O library (fio(3) in AT&T) gets around this by having the function that reads a line return a pointer to the line instead of copying the line into another buffer. There is also another replacement for the standard I/O library: sfio. This package is similar in speed to the fio library and normally faster than the standard I/O library. The package Alloc Stream Interface (ASI) uses mapped files – the mmap function. As with the sfio package, ASI attempts to minimize the amount of data copying by using pointers.